June 14, 2024

“It should have been obvious to [Captain James] Cook and [Molesworth] Phillips that they should retreat to the pinnace immediately. Their lives depended on it. But Cook wouldn’t budge. Perhaps he didn’t want to lose face, didn’t want to appear undignified or cowardly. Perhaps, from all his years spent among the Polynesians, he thought he understood their tides of emotion, their body language, their mentality. Or perhaps, for the first time in his life, he genuinely didn’t have a clue what to do. He had drifted into another world that left him insensible to the dangers pressing in on him. But a warrior broke forward and pulled Cook from his reverie. The man charged at him and raised his pahoa into the air…”

- Hampton Sides, The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook

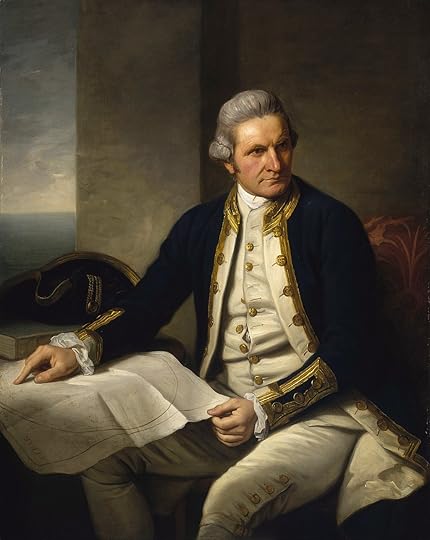

Like many other historical figures, Captain James Cook has had a complex afterlife. In his day – and for years thereafter – he was honored as a great explorer and “discoverer” of lands unknown to the wider world. As time progressed – and as historians finally began accounting for differing perspectives – Cook’s legacy changed. For example, it has been rightly noted that many of the places Cook “discovered” were inhabited islands that had already been found by the people who lived there. Today, Cook has become a symbol of imperialism, a man who – wittingly or not – sailed at the vanguard of colonialism, and all the exploitation that entailed.

In The Wide Wide Sea, Hampton Sides attempts to place Captain Cook into a more nuanced context, somewhere in between flawless adventurer on the one hand, and deliverer of all evils on the other. He also – it should be added – delivers one hell of a tale.

***

The Wide Wide Sea is not a biography of James Cook. Rather, it focuses on his final voyage, which began in Plymouth, England, in July 1776, and ended – poorly – on Hawaii’s Kona Coast in January 1779. During the interim, Captain Cook visited places as different as Cape Town in Africa, Tahiti in the South Pacific, the western coast of what became the United States, and the Bering Strait. The extremes are pretty remarkable, as Cook’s two ships – the Discovery and Resolution – ping-ponged between tropical paradises and the massive ice flows that blocked the much-sought Northwest Passage.

***

As with all of Sides’s books, The Wide Wide Sea benefits from remarkably deep research that is delivered to the reader in readable, often evocative prose. Sides puts you on the quarterdeck with Cook, and on the sun-drenched isles of the vast Pacific, and in the frigid winds off Alaska. His descriptions of the various locales are worthy of a travelogue. Thanks to the incessant demands of my children to be fed and clothed and entertained by Apple products, I have not traveled in a long, long time. So, this aspect was nice.

Beyond the sights, Sides is a wonderful storyteller, with a keen ability to weave fascinating details into the proceedings without slowing its pace. He knows how to deliver a set piece, especially when it comes to Captain Cook’s furious final acts.

That said, this is not a pure narrative. To the contrary, Sides often cuts away for side-discussions about various topics. For example, he spends a couple pages describing the K1 sea clock, which allowed seafarers to determine their longitude with accuracy. At another point, he touches on the ancient Polynesian navigators who managed to reach Hawaii around the year 300, centuries before the invention of global positioning systems or even – for that matter – the K1 clock.

On occasion, Sides also pauses his forward momentum to weigh bits of evidence, and even to referee a fight between two warring anthropologists engaging in one of the vicious nothing-fights that fuels academia. Somehow, he does all this seamlessly.

***

In an “Author’s Note,” Sides promises at the outset to provide a fuller picture of Cook’s expedition, one that moves beyond the observations, declarations, and issue-framing of the white European sailors. This is a promise that Sides fulfills as best he can, given the obvious limitation in documentary evidence.

Whenever Cook drops anchor, Sides is quick to describe the place he landed, and the men and women who were already there. This includes the Palawa of Tasmania, the Māori of New Zealand, and the Tahitians of Tahiti. When necessary, he adjusts or corrects the European version of events by relying on anthropological evidence and oral histories.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing Sides does is to intercut Captain Cook’s arc with that of Mai, a man from the volcanic island of Raiatea. Mai traveled to England, garnered fame, fortune, and mistresses, and then attempted to return home, with unfortunate results. Mai’s journey is every bit as memorable, powerful, and tragic as that of Cook’s, and is a resonant illustration of the possibilities and pitfalls that accompany the meeting of distinct cultures.

***

Unsurprisingly, Captain Cook is the central character of The Wide Wide Sea. Though this is not a traditional biography, Sides does his usual skillful work divining his character. The Cook on these pages has lost a bit of his edge, and perhaps more than a bit of his mental faculties. For whatever reason – and Sides goes through several of them – Captain Cook made a string of dubious decisions, for which he eventually paid a high price.

As noted up top, Sides also attempts to define Captain Cook’s proper place in the historical firmament. Even if Cook was not the first to find the places he is credited with finding, he put them into a global context, which is its own accomplishment. However, as Sides notes, “[i]n Cook’s long wake came the occupiers, the guns, the pathogens, the alcohol, the problem of money, the whalers, the furriers, the seal hunters, the plantation owners, the missionaries.”

Sides can be scathing – and rightfully so – about the actions of Cook and his men. Yet he does this without engaging in self-righteous moralizing, which can get very tedious. Sides suggests that it goes too far to blame all the ills of empire on a single man, especially one whose business was mapmaking, not conquering. Still, he understands that this is a contested view, especially if you are descended from people harmed by Cook’s arrival, and its long, ugly aftermath.

In short, this isn’t a polemic for or against James Cook, though those certainly exist. It is a book that treats complicated matters – such as cross-cultural sexual relationships – as complicated matters.

***

Ultimately, there is no final word on Captain James Cook, and Sides does not bother to try. Perhaps all that can be said of him – without it being contested – is that he was a good sailor. In that, he shared much with the Polynesians before him, who shoved off into the infinities of the seas with little more than a gut feeling that land existed somewhere over the horizon, beyond all that heaving, depthless water.

- Hampton Sides, The Wide Wide Sea: Imperial Ambition, First Contact and the Fateful Final Voyage of Captain James Cook

Like many other historical figures, Captain James Cook has had a complex afterlife. In his day – and for years thereafter – he was honored as a great explorer and “discoverer” of lands unknown to the wider world. As time progressed – and as historians finally began accounting for differing perspectives – Cook’s legacy changed. For example, it has been rightly noted that many of the places Cook “discovered” were inhabited islands that had already been found by the people who lived there. Today, Cook has become a symbol of imperialism, a man who – wittingly or not – sailed at the vanguard of colonialism, and all the exploitation that entailed.

In The Wide Wide Sea, Hampton Sides attempts to place Captain Cook into a more nuanced context, somewhere in between flawless adventurer on the one hand, and deliverer of all evils on the other. He also – it should be added – delivers one hell of a tale.

***

The Wide Wide Sea is not a biography of James Cook. Rather, it focuses on his final voyage, which began in Plymouth, England, in July 1776, and ended – poorly – on Hawaii’s Kona Coast in January 1779. During the interim, Captain Cook visited places as different as Cape Town in Africa, Tahiti in the South Pacific, the western coast of what became the United States, and the Bering Strait. The extremes are pretty remarkable, as Cook’s two ships – the Discovery and Resolution – ping-ponged between tropical paradises and the massive ice flows that blocked the much-sought Northwest Passage.

***

As with all of Sides’s books, The Wide Wide Sea benefits from remarkably deep research that is delivered to the reader in readable, often evocative prose. Sides puts you on the quarterdeck with Cook, and on the sun-drenched isles of the vast Pacific, and in the frigid winds off Alaska. His descriptions of the various locales are worthy of a travelogue. Thanks to the incessant demands of my children to be fed and clothed and entertained by Apple products, I have not traveled in a long, long time. So, this aspect was nice.

Beyond the sights, Sides is a wonderful storyteller, with a keen ability to weave fascinating details into the proceedings without slowing its pace. He knows how to deliver a set piece, especially when it comes to Captain Cook’s furious final acts.

That said, this is not a pure narrative. To the contrary, Sides often cuts away for side-discussions about various topics. For example, he spends a couple pages describing the K1 sea clock, which allowed seafarers to determine their longitude with accuracy. At another point, he touches on the ancient Polynesian navigators who managed to reach Hawaii around the year 300, centuries before the invention of global positioning systems or even – for that matter – the K1 clock.

On occasion, Sides also pauses his forward momentum to weigh bits of evidence, and even to referee a fight between two warring anthropologists engaging in one of the vicious nothing-fights that fuels academia. Somehow, he does all this seamlessly.

***

In an “Author’s Note,” Sides promises at the outset to provide a fuller picture of Cook’s expedition, one that moves beyond the observations, declarations, and issue-framing of the white European sailors. This is a promise that Sides fulfills as best he can, given the obvious limitation in documentary evidence.

Whenever Cook drops anchor, Sides is quick to describe the place he landed, and the men and women who were already there. This includes the Palawa of Tasmania, the Māori of New Zealand, and the Tahitians of Tahiti. When necessary, he adjusts or corrects the European version of events by relying on anthropological evidence and oral histories.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing Sides does is to intercut Captain Cook’s arc with that of Mai, a man from the volcanic island of Raiatea. Mai traveled to England, garnered fame, fortune, and mistresses, and then attempted to return home, with unfortunate results. Mai’s journey is every bit as memorable, powerful, and tragic as that of Cook’s, and is a resonant illustration of the possibilities and pitfalls that accompany the meeting of distinct cultures.

***

Unsurprisingly, Captain Cook is the central character of The Wide Wide Sea. Though this is not a traditional biography, Sides does his usual skillful work divining his character. The Cook on these pages has lost a bit of his edge, and perhaps more than a bit of his mental faculties. For whatever reason – and Sides goes through several of them – Captain Cook made a string of dubious decisions, for which he eventually paid a high price.

As noted up top, Sides also attempts to define Captain Cook’s proper place in the historical firmament. Even if Cook was not the first to find the places he is credited with finding, he put them into a global context, which is its own accomplishment. However, as Sides notes, “[i]n Cook’s long wake came the occupiers, the guns, the pathogens, the alcohol, the problem of money, the whalers, the furriers, the seal hunters, the plantation owners, the missionaries.”

Sides can be scathing – and rightfully so – about the actions of Cook and his men. Yet he does this without engaging in self-righteous moralizing, which can get very tedious. Sides suggests that it goes too far to blame all the ills of empire on a single man, especially one whose business was mapmaking, not conquering. Still, he understands that this is a contested view, especially if you are descended from people harmed by Cook’s arrival, and its long, ugly aftermath.

In short, this isn’t a polemic for or against James Cook, though those certainly exist. It is a book that treats complicated matters – such as cross-cultural sexual relationships – as complicated matters.

***

Ultimately, there is no final word on Captain James Cook, and Sides does not bother to try. Perhaps all that can be said of him – without it being contested – is that he was a good sailor. In that, he shared much with the Polynesians before him, who shoved off into the infinities of the seas with little more than a gut feeling that land existed somewhere over the horizon, beyond all that heaving, depthless water.